F irst impressions are crucial. People often remember how they first met someone, what they seemed like, how they acted. Opinions of other people, their character, and their motivations are often formed in the first few minutes, and certainly within the first few days of being around them. Whether relationships are begun or ignored, whether a potential job candidate is hired or overlooked, and whether a person’s communication is deemed trustworthy or dishonest is often decided upon by first impressions. People rarely even get a chance to reevaluate those opinions, as all subsequent interactions are often seen through the lens of that first encounter.

But rarely are first impressions so important as when the unexpected is happening. When something new and surprising is beginning, people’s senses are heightened and each detail gains microscopic clarity. Those impressions, whether true or false, often last a lifetime.

I’ve thought about this long and hard, before coming here to Nosy Mitsio and ever since. If this is not an instance of the new and surprising, the unexpected, then what is?

G od has called us here to this distant and remote corner of the world, to join him in an outreach to the Antakarana people. There are no churches here on Nosy Mitsio, no Christians. In Madagascar’s northern towns and cities, where the Antakarana are sometimes exposed to churches established by other tribal groups, very rarely will an Antakarana person ever enter the front door. When short-term attempts have been made to introduce the Gospel specifically to the Antakarana, the presenters usually receive a quick reply that it’s not necessary, that the Antakarana already have a vow they’re keeping to their ancestors and anything else is taboo. The Antakarana, through their ancestral vows, are committed Muslims, even if few of them have any idea what that means.

As far as we know, we and our team are making the first ever attempt of any missionaries to live long-term among the Antakarana people in a traditional rural setting. Not only that, but here on Nosy Mitsio is where the Antakarana people fled during Madagascar’s tribal wars, shortly after making their vow to become Muslim if they’d only survive long enough to uphold it. This is the place where their people escaped destruction, where they gained a new lease on life. Can this also be the place where the Antakarana find the new life that only Jesus brings?

There’s no doubt that what we desire to see happen among the Antakarana people is something brand new, something surprising and unexpected. So how can we establish a true new beginning among these people? How can we accurately present Jesus to them? And how do we start the whole thing off, so that when the people of Nosy Mitsio see a group of weird foreigners moving in to their villages, that the crucial first impression they receive is one that communicates Jesus? I’ve thought about this long and hard, and now that my family has been living here on Nosy Mitsio for eight months, I can reflect on it too.

For me, it all begins with Jesus himself. We’re communicating a person, not just a message. So what does that look like?

G od had a lot to say to people throughout the Old Testament and he used a wide variety of ways to do it. But apparently a lot of it wasn’t getting through too well and God decided that sending messages wasn’t enough. He himself would become the messenger. And man, how he surprised everyone when he did it!

The God of all Creation joined Creation and became a little vulnerable baby born to an insignificant family. And then he lived for about thirty years, a life presumably normal for his circumstances, without much of anything of note happening. It was only the last and shortest phase of his life that he focused on speaking his message and then participated in two of his most powerful acts: his death and resurrection.

But how strange it is that God should do things this way! Why didn’t he just ride down from heaven in a flaming chariot or a hovercopter or something cool and powerful like that? Then he could have just spoke his message in a loud booming voice from the skies above everyone, having his angels go to each group of people and translate for them, and he could’ve just told them how things are going to be! It would’ve been quick and easy and surely everyone would’ve listened. How could we not listen to a display like that?

I’m sure we would’ve all listened. But what would be the message we’re receiving? When God became man, he was telling us a lot about himself, his character, and his message. But he’s also telling us a lot about what he thinks of us. When he says he loves us, which demonstrates it more: the easy thing or the hard thing? When he says he cares about us intimately, every detail of our lives, what makes us consider his message: that he himself was born as a helpless baby in one of our villages, or that he could list off the principle facts of our history? When he says he’s given us value, that we’re the trouble-making son (or the proud older brother) who he’s wanting to welcome back with open arms and a great party, what communicates it better: him taking the time to live our lives, or him shouting at us from a loudspeaker? If he wants to stir us from our complacency, help us realize the great destruction we’re causing ourselves and our whole world, what makes it hit home: that he would go before us and die a death like ours, or that he’d simply enumerate the punishments for our crimes? If he says he’s got something new and better than we’ve ever experienced, how in the world can we believe that, except that he rose again to show us the humanity he’s been crafting all along?

J esus didn’t just tell us God’s message; Jesus IS God’s message, every aspect of his life. If we believe Jesus also came for the Antakarana people, and we do, then Jesus was also born among them, grew up in their customs and traditions, and when he became a respected member of their community, he showed them a better way to live, the truths of who God is, the reality that would make them whole and give them new life at last, for all who choose to follow him. And every minute of his life, from his birth to the way he died and the way he lives again, is a demonstration of all of that.

Jesus is God “incarnate”, God “made flesh.” So when we’re communicating him (not just about him), I think we also need to model him. That has a huge impact on the way we choose to live. Not just the first impressions we give, but our whole ministry, should be “incarnational.” We should strive through our lives and actions and eventually our words to show to the Antakarana people who Jesus is: the radically unexpected reality that he was also born for them, among them, took the time to know them, and reveals the fullness of God’s love and truth for them.

So I’ve long known that the first impressions we present should somehow reflect the incredibly surprising humility of Jesus’s birth. Obviously we can’t physically be born again as babies, the way God was. So I’ve had to think about different ways we could still represent Jesus’s birth, and they all boil down to a few basics: living like the people here live, doing things the way they do it, and in any and all things, being the ones who are powerless, weak, and dependent – just like a baby is, just like Jesus was. Looking back on all this brings me to the reason I’m writing today about first impressions: man, we’ve failed pretty miserably.

Quenching our thirst with coconuts on the long hike from the south to the north on my second trip to Nosy Mitsio.

I t started with a survey trip a year and a half ago. We needed more information, we needed to confirm some details, and because of the schedules of the various people involved, we had a short window of opportunity to do that. So the only choice on the table was the choice we all took: we came like tourists. We came from the route that only tourists come from, we came on a speedboat that no one here ever rides on, we showed up with translators/guides (because of the massive difference in dialect), we stayed in a rarely used tourist bungalow, and we even had a cook to prepare food for us. And we did it all in less than a week. We may have asked a few probing questions about life and we tried to explain our project to begin the following year, but there was no doubt to everyone here that we were just like all the other foreigners they’d ever seen or heard of.

Our next follow-up was just me and a couple Malagasy friends many months later. I didn’t give myself nearly enough time, but I found the normal route of access to Nosy Mitsio, we sailed to get here, and I walked across the island and relied on the hospitality of strangers. But everyone still remembered the first impressions we gave when we came like tourists and it was clear they weren’t treating us the way they might have otherwise. If me and my friends weren’t obviously very hungry, very thirsty, and still had a long distance to walk, we may not have experienced any normal hospitality at all. I was hoping to change some first impressions with my second ones, but I don’t know that I made any real impact.

Going forward from there has just been a mixed bag. My family and I moved into a tiny, shambling hut, of lower quality than most everyone else here on Nosy Mitsio. But at the same time we brought a contractor and his work crew and a lot of materials to start building our long-term home, and we rented a full boat (along the local route) to transport many of these materials here. All of these are signs of great wealth and power and the local people rightly associated those things with white foreigners, even if we were acting a bit odd compared to the tourists they’ve seen.

When we should’ve been immersed in learning the new dialect, instead we were selecting sites, sourcing materials, and finding workers. When I should’ve been helping people cutting leaves or preparing coconuts, instead I was negotiating deals for roof thatching or wood flooring, trying to be sure I wasn’t being cheated like a foreigner when everyone still saw me as one. When we should’ve been working alongside the people in their rice fields, instead we were making boat trips back and forth to the mainland carrying building materials for our team homes.

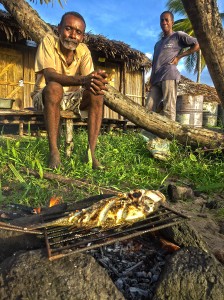

There are times when we’ve attended big cultural ceremonies and times when I’ve been fishing with the king, and we’ve picked up a decent bit of Antakarana dialect just out of necessity for daily life. We’ve struggled on numerous local boat trips with our fellow villagers, drifting on the ocean or being tossed by the waves. But now we own our own team boat, one very similar to, but superior than any of the local boats. Sure, it’s a necessity for greater safety and scheduling, but we know what it communicates. We now have stocks of food like no one else (though we also don’t own any rice fields or cows, goats, or chickens like they do). Matimu himself is far more “incarnate” than Lora or me, as he blends right in playing with the kids and no one feels ashamed in his presence. But the first impressions we gave, and the impressions we’ve tried to mold since then, have been very mixed messages with probably very little of the shocking reality of Jesus’s incarnation.

S o I’ve struggled with these thoughts for months now, and I’ve seen how these things have played out in our local relationships. Sure, it’s all different for Jesus. He’s God (and man), and I’m only man. So how could I think to do the same? Besides, most of these inconsistencies have been because I’ve been doing things that have had to be done: making sure that we have a place to live, and that our team members will too by the time they arrive here. And some of the local people’s “first impressions” of us, as white-skinned foreigners, existed before they ever saw us and much of what we’re experiencing now may have been inevitable to begin with. There’s no hiding how we look and what the local people “know” about people who look like us, no matter how hard we try not to fit the mold of their expectations. Then again, nobody expected Jesus (the Messiah) to come like he did either, but I guess what’s different is that most people just didn’t believe it was him until he rose from the dead.

I don’t have an answer for most of this, though it’d be so much easier if I did. We just haven’t lived up to our expectations for ourselves and we’re afraid we’re misrepresenting Jesus. But we’re here now. We’re still following God and we still believe he’s acting and will act for the Antakarana people here. Ultimately, it’s God who will reveal himself, and he’s chosen imperfect people, like ourselves, to do it through.

People here have seen us struggle. They’ve seen me cry out in pain when I’ve been sick. They’ve seen us worry when our food supply was eaten by goats or mice. They’ve seen us fumble over new words and try and try again to learn to use them correctly. They’ve seen us make horrible cultural blunders, accidentally breaking taboos and not saying the right things at funerals. They’ve seen us scared of waves and weather, bouncing around together in small boats. They’ve laughed as I leaned the wrong way and the little canoe I was on with the king flipped over in the ocean. And they’ve heard us bemoan our inability to spend more time in the fields with them, to have language lessons with them, to spend more time learning their history and their ways.

Maybe that’s something. After all, when Jesus was born, he surely cried out. He struggled and he relied on people around him to help him out. He was a baby. In Jesus, the beginning was crucial. Not only did it show who he is and serve as the model for his life to follow, not only did it show so much about God’s character and the depths of his love for us, but it was also the beginning of all of our new beginnings. By the same form that Jesus brought salvation to us, so he also works it in our lives. We have to be born again like him: in humility and weakness and on the full dependence of others, depending fully on God himself.

S ince we’ve moved to Nosy Mitsio we’ve become more and more acutely aware of our own limitations, our own lack of skill or knowledge, our own lack of the very things we need to live here and adapt well into this community. In our personal weakness and our dependence on others, we have become like babies again; constantly relearning what we thought we knew about language, about life, and about how to represent Jesus to people who’ve never known of him. All of this just gives fresh ground for God’s new beginnings to take hold in our lives, to be more deeply rooted, and to grow into the new creation in which he’s forming us.

By God’s grace, maybe some of our fellow villagers here have seen some of that process in our lives. In our struggles and weaknesses and shortcomings, maybe they’ve caught a glimpse of the all-powerful God who became a helpless baby. And in the ways God has grown us since moving here, maybe they can see a little bit of his power to transform even the most stubborn of people. Maybe in both our imperfections and our persistence, even in the confusion of the mixed message we’re surely sending, maybe they can sense that something new is beginning, not just in us, but also for them.

So we shouldn’t despise new beginnings in our lives. Every time we’re torn down and broken apart is a chance for God to build us back up again, into new creations. And though we may often be ashamed of those around us seeing us at our weakest points, it can be just one more way that God can, through our lives, reveal his character and the truth of Jesus. After all, he who is our model wasn’t ashamed to be born a baby, to cry out in pain and surprise, to be at his weakest around all of us. In him are our new beginnings, new life for all who follow him.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks